I was a lousy athlete, but I have always loved baseball.

I was always a round little kid, then a somewhat round, clumsy teenager. I just didn’t have the speed or agility for most sports. My football career lasted perhaps two hours, since I was placed on a team where most of the kids were significantly older than I was, but closer to my physical size. I was somewhat used to being bullied, and having to defend myself in an appropriate manner, so imagine my surprise when I was told that punching an opposing team mate was not an acceptable response to a hit on the line (at least it wasn’t in the 1970s).

I was the only member of my basketball team never to score a basket when we went to (and lost) the state championship, but I led the entire league in assists. In that case, my size played to my advantage, since even without trying I intimidated a lot of other kids my age.

But baseball was what I loved most, and it was what I tried my best to master.

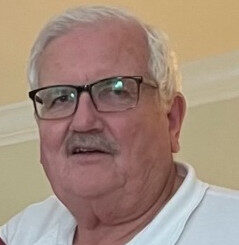

I come from a baseball family — my brothers played, my uncles played. Papa coached and managed semi-pro ball teams starting around 1940, after having played high school and league ball. He loved baseball, and began teaching me about America’s game from a young age. He recognized my shortcomings, but never stopped encouraging me to aim long and hard.

When I began playing organized ball, I was relegated to a far corner of right field, and the long distance end of the batting lineup. I had to be a long ball hitter, since I was just too slow for speed. When I connected with the ball, most of the time it was gone. But I had to connect with it first. My heart was in the game, even if the body wasn’t fit for it. Eventually, someone put a gun in my hand and I discovered my own sports of hunting and target shooting, but those are a column for another day.

Papa was disappointed, but he understood. We still went to ballgames — Legion ball was strong back then, and sometimes the competition in church league softball made the major leagues (and many preachers) blush. Maybe once a year, we went to Durham and later Fayetteville to see the Bulls or the Generals, back before the latter began changing names and owners like their players change socks.

The greatest of games, however, were the ones we found whilst driving around on a Sunday afternoon.

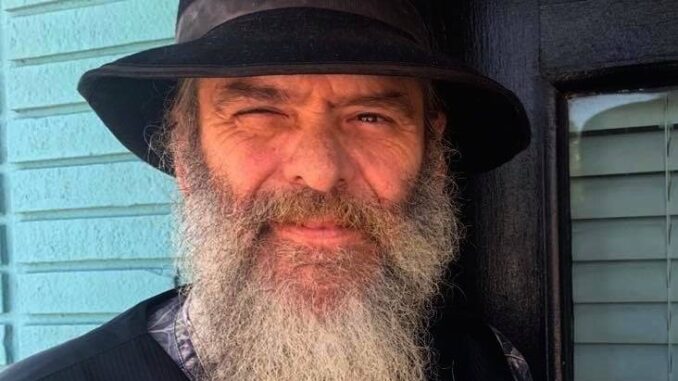

One particular field was somewhat like the village of Brigadoon in the old movie; we were only able to find that clay field once or twice, after which it seemed to either be abandoned or to have simply vanished. On this particular day, however, it was as busy by comparison as many major league ballfields.

The outfield was a mixture of Johnson grass and plain old weeds, mowed to a uniform length by hand and the infield was the native red clay, dragged by a tricycle tractor somehow given time off between tobacco and corn. The ballfield itself may have been a cow pasture or farm field in another time; it was nestled in a stretch of pine woods, off a dirt road, and other fields in the area were relegated to more practical things like crops and cows. There was a graveyard of local names off to one side, some of the stones long since worn smooth, others tagged with little metal placards used to mark a final resting place until a stone can be purchased. Some of the graves had once had wooden markers, or so I heard later on.

I cannot recall exactly why a hundred or more folks in pickups and older cars had gathered at this place on a scorching July Sunday after Independence Day, but they welcomed us. There were perhaps a half-dozen other faces in the crowd who were not African-American, including a sheriff’s deputy Papa knew (and who played Legion ball).

One of the pickups had a cover for selling vegetables from the owner’s garden, but on this day he was doing a brisk business in canned soft drinks (and possibly some cans of something a little stronger, but no pesky questions were asked about permits and such). Those whose constitution couldn’t bear either sparkling beverage were welcome to make use of a pitcher pump with green-mossed boards forming a rough table, and a lard can hard by for priming.

There were no bleachers, just roughcut plank benches, lawnchairs, and ladder back chairs stolen from country kitchens.

If memory serves, after 40-plus years, the baseball teams were comprised of a family going against co-workers from a farming operation.

There were no uniforms, aluminum bats, or batting gloves. Instead there were old bats, some store bought Louisville Sluggers or other brands, even one or two that were possibly homemade, and some with electrical tape carefully repairing a break or crack. The balls were fairly new, but the gloves were an admixture of the latest model sporting Johnny Bench’s signature to the old five-finger “paws” my father grew up with, gloves worth hundreds to collectors nowadays. One team played without shirts, since there was lack of uniforms and numbers. A preacher was umpire; Papa later remarked that he had to be fair, or collections might bedgown the next Sunday.

I have never been to a ballgame in a major league park, but I cannot imagine it being even a tenth as special as that day down a country road.

One of the shirts had a wicked fastball, as well as a curve that would make a statue duck; when one skin player was at the plywood plate, the crowd roared with encouragement as well as catcalls. Apparently the two had played against each other before, and when the batter leaned into the curve, rather than instinctively dodging it, there was a solid crack as he connected and sent the ball into the pines over center left field. The outfielders ran after it, but their pace slowed as the reached the rough “fence” line painted in housepaint. They were replaced by a swarm of boys younger than me who appeared from nowhere. They reappeared victorious, bearing the horsehide grail. The one who claimed to have found the ball received a longneck bottle of Coca-Cola, dripping ice from a battered cooler.

The runners on second and third crossed the white plywood plate with ease, and the hero who drove them in almost casually jogged around the bases, smiling at the pitcher, who smiled back and pointed a half-threatening forefinger.

Papa was able to relate to some of the older men there, and their conversations turned to the giants of the diamond from the 20s and 30s; it wasn’t just about Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb and the DiMaggios, either, but about players in the leagues of the segregation days, of white players who refused to play with blacks, blacks who passed as whites, and Native Americans who could outplay them all. To my Old Man, baseball was baseball, and the Negro League was as important as the National League. The mutual agreement was that there was no reason to separate the races in baseball, but there were sharp opinions about which player could have out pitched or outhit the other.

I do not recall who won — we found them late, and only saw five or six innings — but I do recall when it was over, everyone shook hands, laughed and pounded backs. There was joshing and teasing and joking, along with warnings of what would happen when next they met.

We made our departure before the baskets and boxes of food were brought out. Several of the folks, especially the ladies, recognized Papa as the “Newspaper Man,” but the Old Man didn’t want to overstay our welcome. I got hugged and handshaken, as did Papa, and we were repeatedly told to come back.

I was talking with a buddy of mine the other day about Dixie Youth ball; his boys love playing it, but the pandemic chopped their season short like a fast shortstop on a hot ground ball. He speculated that baseball, like his service in the military, cured him of any prejudice he had as a child and a teen, and he was making dang sure his boys grew up the same way. When the kids are playing baseball beside children of all races, there are no races. Just teams and teammates.

I don’t think baseball could solve all the world’s ills; after all, there are plenty of kids out there like I was, kids who are poorly suited for athletics, or just don’t have any interest.

At the same time, I think a lot of today’s problems could be solved if we all learned to sit in the grass together by a homemade lot on a Sunday afternoon, or even took to the diamond for a little competition, just people enjoying America’s game.